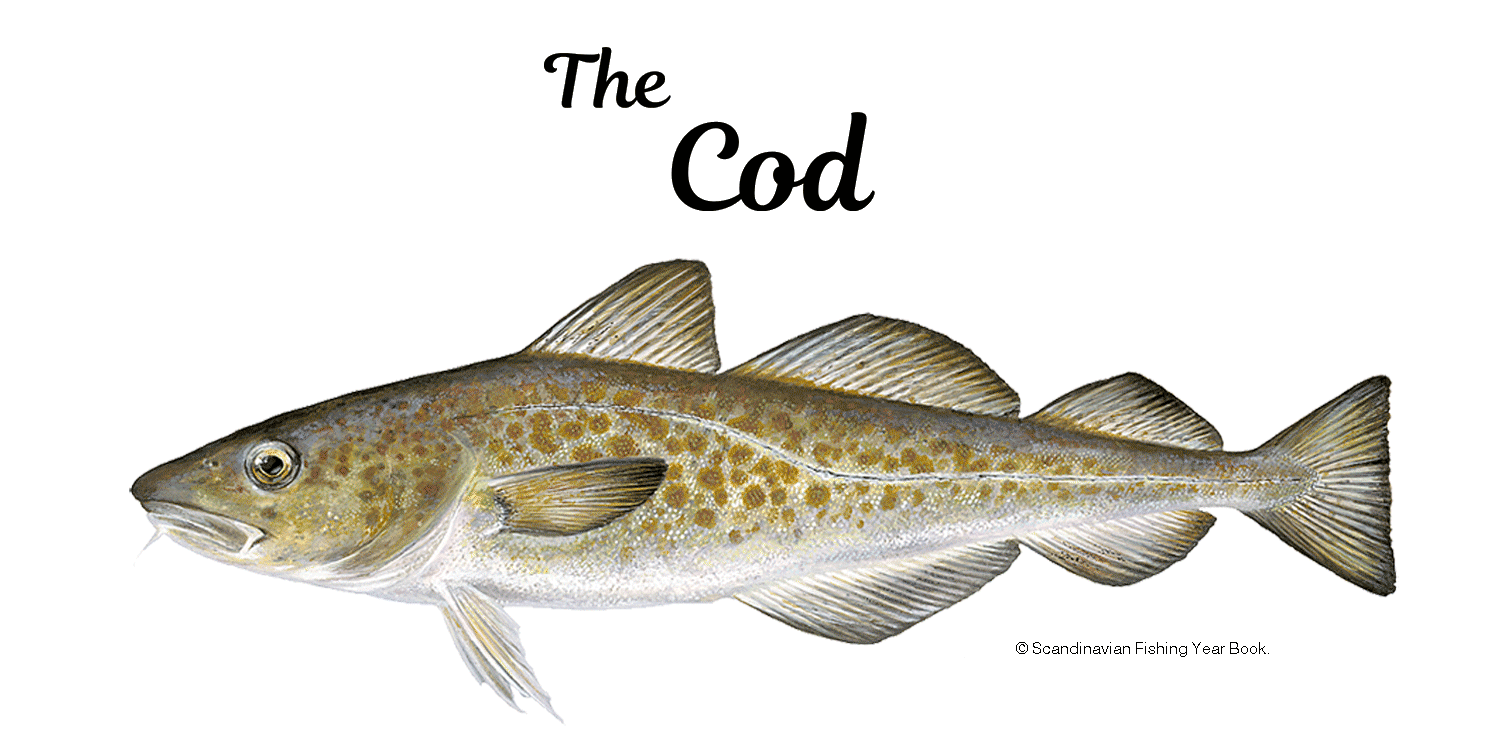

The Atlantic Cod - Gadus morhua - our nations favourite white fish. The Stone Age neanderthals feasted on them, salted and dried the mighty Vikings were fuelled by them on their many epic longship raids of murderous pillage and plunder. The Atlantic Cod has been through the wars - and lives to tell the tale.