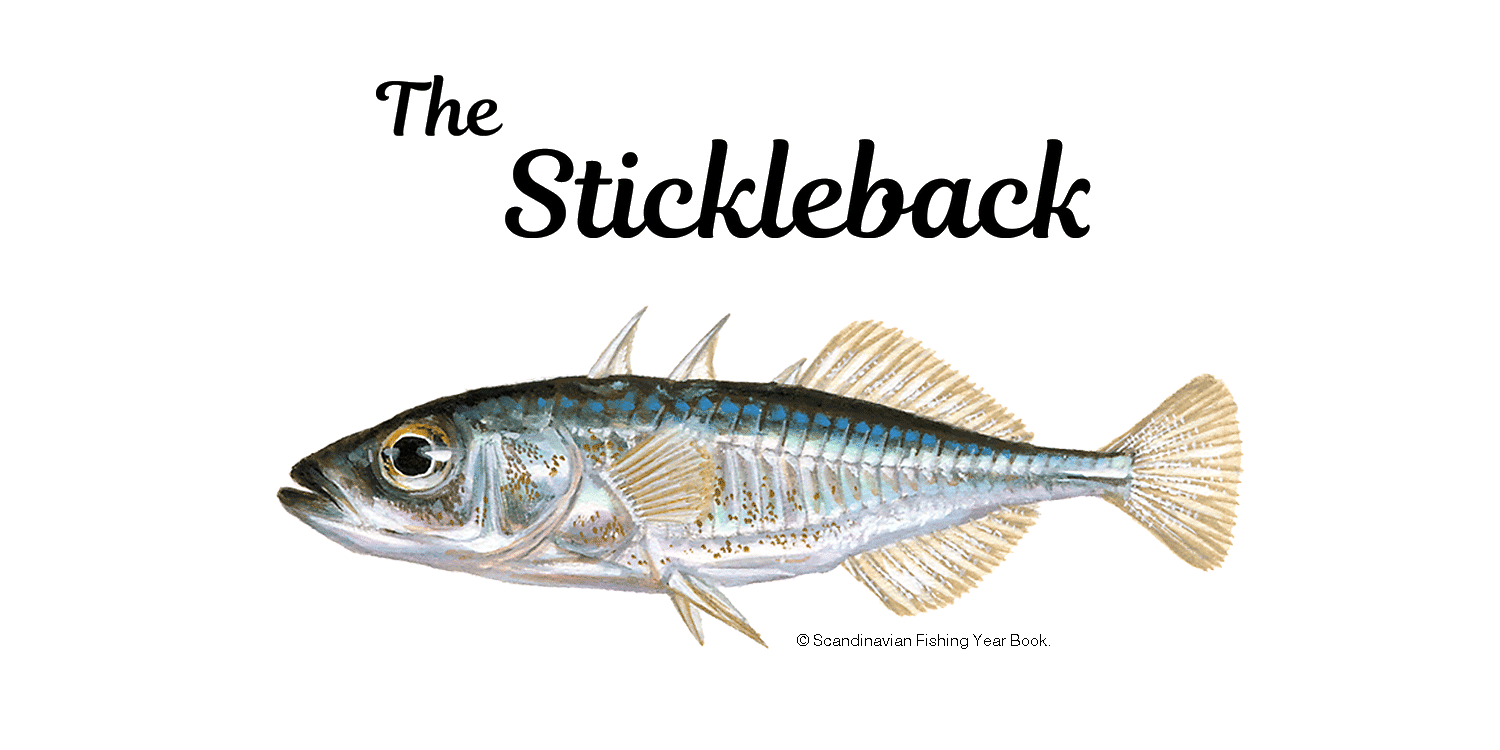

Easily recognisable, three spined sticklebacks are the smallest of all the freshwater fish which inhabit the British Isles growing to an average length of only 7 centimetres. Despite reaching such modest dimensions it is nevertheless an extremely aggressive predator, feeding on invertebrates, tadpoles and smaller fish.

At all times when fishing for Stickleback think like a Stickleback ~ no matter how weird it gets !