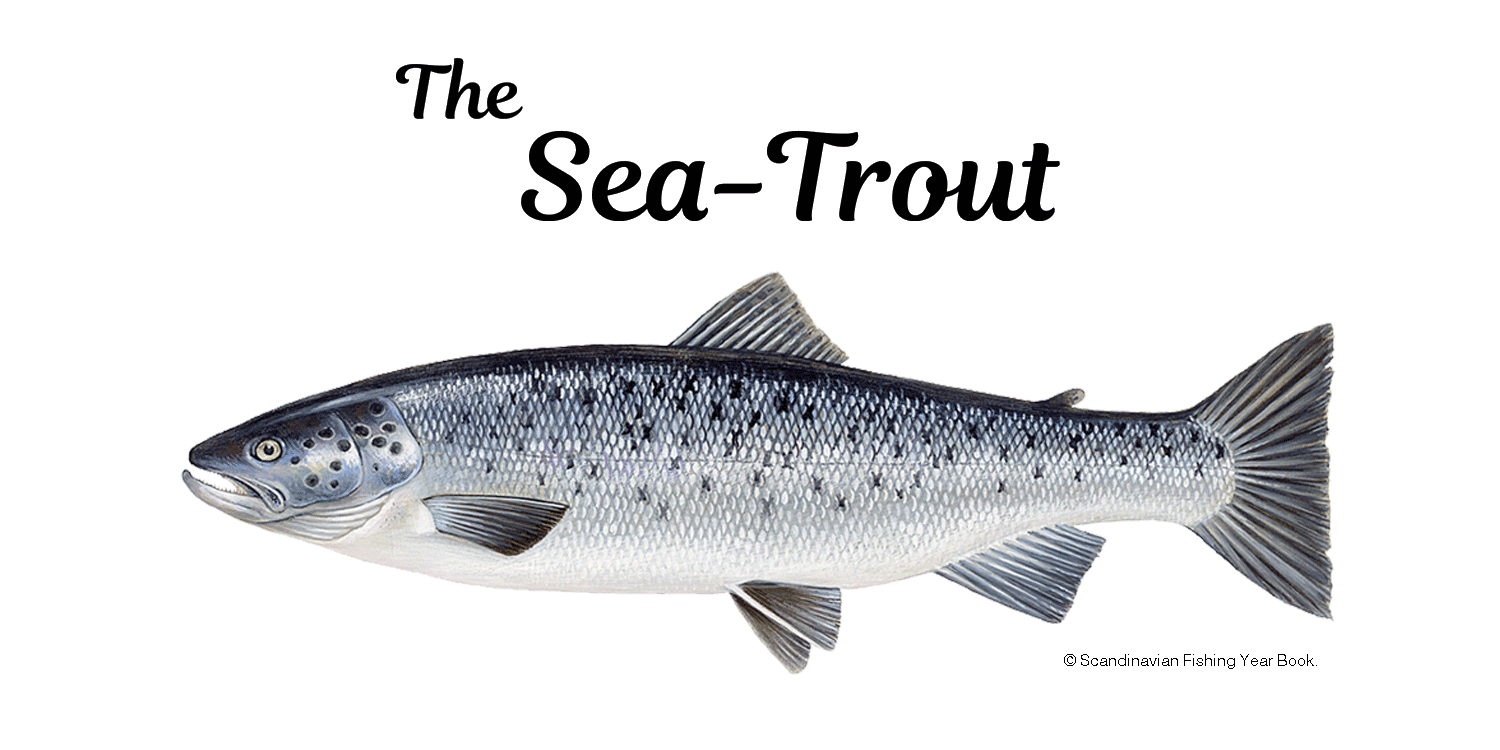

With salmon tagged the “King of Fish” perhaps "Prince of Darkness" befits the nocturnal Sea Trout as it glides ‘tween the tides through the shadows of night. Easily spooked during daylight hours when darkness cloaks the land this highly prized silver torpedo is a worthy adversary for any angler wild enough to target them.