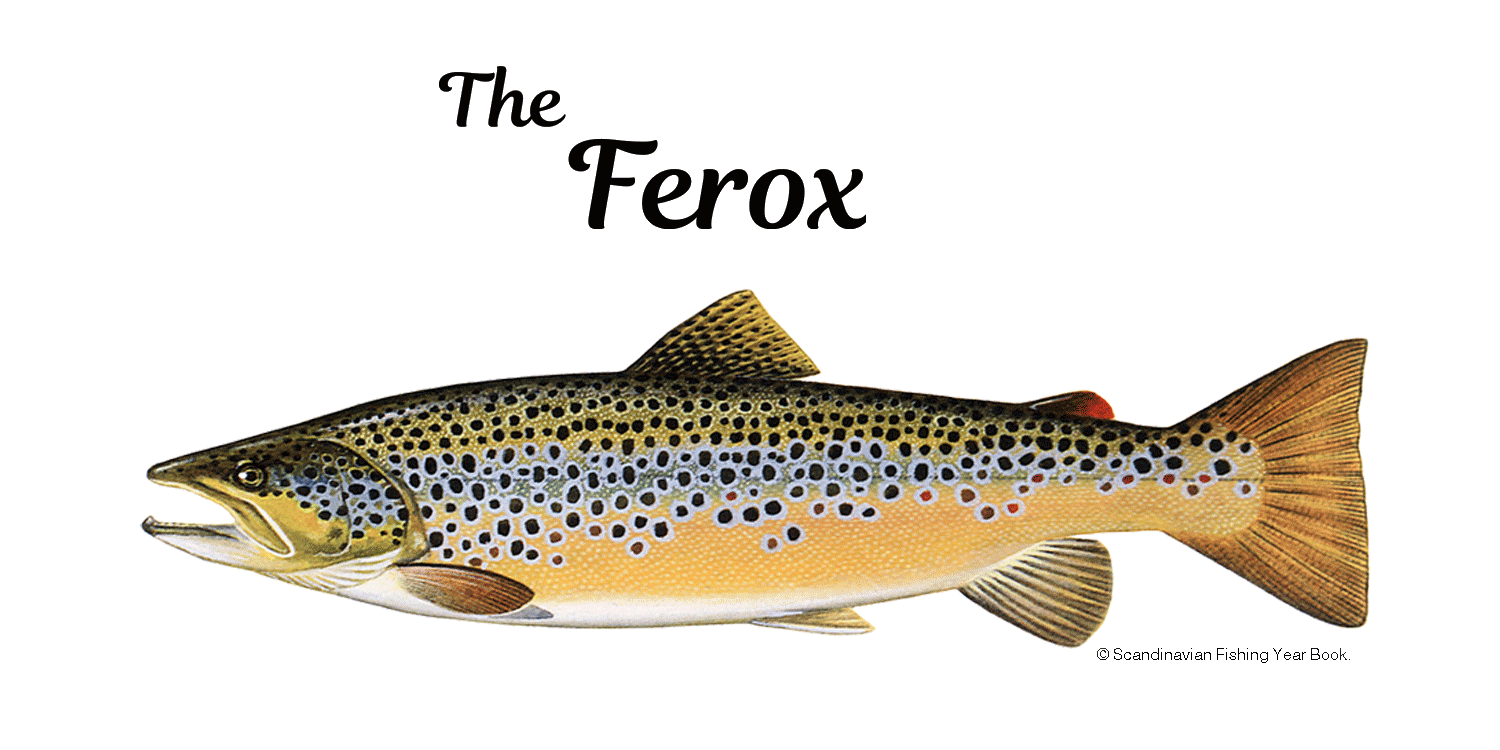

As far back as 1835 the renowned Scottish angler and naturalist Sir William Jardine, believing the large cannibalistic trout he caught during his visits to Sutherland in the Scottish Highlands to be a distinct separate species, christened them “Salmo ferox”.

A rather apt and fitting name given that ferox is latin for wild, spirited and fierce.

Quite incredibly, given the passing of over 180 years, very little light has since been shed on these fascinating and mysterious fish of legend.

One thing that is understood is that apart from our resident populations here in the freshwater lochs of Scotland and Ireland they are widespread, ranging as far afield as Scandinavia and Western Russia displaying wide variation of shape, spot markings and colouration.

FEW SPECIMENS FOR DATA

Undoubtedly one of the major obstacles in conducting more detailed scientific research is the considerable difficulties in collating data when there are so very few specimens available to study.

When you take into consideration the volume of water within the large lochs they inhabit and the very low numbers of resident ferox then it becomes easier to understand and appreciate the difficulties involved.

Yet another obstacle to overcome is that given the deep water they generally inhabit the only really viable method of capture is by rod and line and even the most dedicated, specialised, persistant and hardiest of ferox anglers catch very few fish between them.

Take note, the hunt for Samo ferox is most certainly not for the faint of heart !

Estimations of actual large ferox present in Loch Rannoch make particularly depressing reading with numbers in 1994 thought to be as low as 111 whereas in 2009 that number is believed to have dropped yet further to possibly as few as just 71 fish.

These figures bring into very sharp focus indeed the urgent requirement for anglers to ensure any ferox caught are handled with extreme care and carefully released safely and unharmed.

SEPARATE SPECIES

Whether or not ferox should be considered a separate species from the brown trout has long divided scientific opinion.

Although ferox were once classified as an entirely separate species, Salmo ferox, this is no longer the case and they have now reverted to their earlier brown trout classification of Salmo trutta.

That being said and to add yet further confusion, there are some lochs where ferox have been recognised as being not only behaviourally different but also genetically distinct from the other resident brown trout in the same loch.

In 2006 further evidence was found to suggest that ferox trout from both Loch Laggan and Loch Awe in Scotland, along with Irelands Loch Melvin, whilst still belonging to the same resident species, have diverged sufficiently with different diet, chosen habitat and mating preferences to have led them to become reproductively isolated from the other brown trout within the same water.

These ferox trout now collectively form a “clade” (monophyletic group) which in turn means they fall into a group of fish that share a single ancestor and an unbroken evolutionary line of descent.

With this in mind some of a scientific persuasion have called for the earlier classification of Salmo trutta to be revisited and the Salmo ferox classification reinstated.

It seems that even with the many advances in our genetic testing capabilities that scientific opinion currently remains divided and unable to reach a definitive conclusion.

Whatever the truth the term ferox remains and is now commonly used to describe these large, voracious and predatorial, long lived trout that inhabit our highland freshwater lochs.

GENERAL DIET

Juvenile brown trout, including the young ferox, begin their lives as Benthivores - feeding on invertebrates and insects - however once a length in the region of 30 to 35 cms is achieved ferox switch and become almost exclusively Piscivores - fish eaters.

Once this change occurs they begin actively seeking out, hunting and pursuing their prey, usually arctic charr, rather than lying in ambush like our old wily friend Esox lucious, the pike.

The timing of this change of diet in the ferox is believed to be triggered specifically by their currently attained size rather than by their age.

Whatever the cause of this dramatic dietary change from insects to fish might be this switch, to such a very high protein diet, now results in exceptionally rapid growth and longevity.

Close examination of their scale rings have shown clear evidence of this dramatic size increase not only in their growth rate but also in the overall weight they are now capable of reaching.

Studies have also concluded that the young offspring of the Piscivorous ferox trout not only grow much quicker but also show more aggression in comparison to the progeny of similarly sized Benthivorous trout within the same water.

Such boldness will in all likelihood enable the young ferox to take up station earlier in areas of the loch where better feeding prevails.

Whilst arctic charr, when available, are of major importance in the diet of ferox, other fish such as whitefish, perch and indeed their own fellow brown trout are also readily taken.

The ferox is also known to be able to change its primary prey selection as and when required such as when arctic charr became extinct in Loch Corrib in Ireland, due to the introduction of roach, the ferox thereafter switched to a predominantly roach diet.

Ever the opportunist ferox have also been known to congregate around loch outflows during the salmon smolt run.

LARGE FEROX

Once the ferox trout begins its fish eating phase growth is rapid.

In 1998 one tagged fish from Loch Rannoch, which when previously caught four years earlier in 1994 had weighed 3 lb. 8 oz., now weighed in at a whopping 14 lb. 4 oz., which equates to an increase of 10 lb. 12 oz. and a quadrupling in weight in just four years !

With ferox attaining such weights it is easy to understand how these freshwater leviathans had become the stuff of legend and a favourite quarry of our own Victorian forebears.

The British rod caught ferox record currently stands at 31 lb. 12 oz.(14.4 kg.), this fish was caught on Loch Awe in Argyllshire on the 15th of March, 2002.

Its important to remember that whilst our ferox grow large only a very small percentage of trout in a loch are ferox.

To date the oldest recorded ferox was one taken from Loch Killin in Inverness-shire with an age estimated to be in the region of 23 years with other notable captures of 18 years and 17 years respectively from Loch Rannoch and Loch Garry.

SPAWNING

The generally accepted view is that until they reach a size large enough to switch to their predominantly fish diet and with that subsequently undergo dramatic growth the ferox forego spawning.

This not only gives them a higher survival rate but also greatly increases fecundity with the additional advantage that their eggs are now of a much larger size.

The areas chosen by the spawning ferox are generally found to be at the major outflow and inflow of rivers and given the scarcity of suitable spawning sites any form of pollution or other detrimental intrusions can wreak havoc on the chances of spawning success.

Dramatic fluctuations in water levels caused by hydro-electric development can cause disruption to the waters natural flow and damage the critically important gravel substrate of the spawning redds seriously impacting the survival rate of both the eggs and alevins.

ROAMING RANGE

Data collected and collated from several lochs, including Lochs Rannoch and Garry, have shown ferox to be largely non-territorial ranging over wide areas of the loch during the hours of daylight.

During this time they were mostly found to frequent depths of less than 30 feet although on occasions the radio trackers recorded them making sustained dives to around the 100 foot mark whilst they presumably pursued and harried shoals of charr.

Once darkness cast its shadow the ferox become much less active and moved into the shallower loch magins.

LOCH RANNOCH

Over the years various studies have been undertaken on several of the large “oligotrophic” - nutrient poor - Scottish lochs that hold ferox with one of the most interesting being that from Loch Rannoch in Perthshire, Scotland.

Although only the ninth largest in Scotland, Loch Rannoch is nevertheless a massive expanse of water somewhere close to ten miles in length and one mile wide with a depth of 440 feet and a circumference of twenty two miles or thereabouts.

With its long history of captured ferox it was a natural choice for scientific studies.

Angling data has been recorded for several decades with particular focus on captured ferox and their weights, sadly this has also monitored their dwindling numbers.

I will try to collate the data as best I can with my apologies for attempting to distil decades of hard scientific graft into just a few paragraphs.

Angling methods generally concentrated on both large lures and dead baits, mostly arctic charr and brown trout, that were trolled at different speeds and water depths utilising various bait mounts that imparted a movement to the bait akin to that of an injured or stricken fish.

Fish finding echo sounders were employed to try and build up a more detailed picture of the lochs underwater features such as the depths, contours and drop offs along with any particularly interesting areas that might possibly hold ferox.

Given that no genetic data was available at the time, the size of trout captured - and recorded as being ferox - were of a length equal to or above 40 cms, a point at which it was considered safe to presume that in all likelihood they would have already switched to a Piscivorous diet.

Considering these captured and recorded trout were caught on large trolled lures and sizeable dead baits also gives a fair degree of credence to the belief that these fish were indeed ferox and not Benthivorous trout.

During the research it was found that a surprisingly high proportion of previously tagged fish were being recaptured suggesting there were a relatively small number of these large resident ferox in the loch.

Estimations of ferox present in Loch Rannoch makes for particularly depressing reading with numbers in 1994 thought to be as low as 111 whereas fifteen years later in 2009 that number is believed to have dropped yet further to as few as just 71 fish.

These figures bring into very sharp focus indeed the urgent requirement for anglers to protect the ferox and ensure they are handled with extreme care before being carefully released safely and unharmed.

Interestingly Loch Rannoch is not only home to brown trout and ferox but also contains Atlantic salmon, sea trout, pike, perch, three spined sticklebacks, eels and minnows as well as three ecologically and morphilogically distinct forms of arctic charr.

Similar studies undertaken at Loch Awe in Argyll and Bute, Scotland, have found that its ferox, which are genetically distinct from the other trout in the loch, become Piscivorous at just one or two years of age in comparison to ferox from Loch Rannoch or Loch na Sealga in Wester Ross, who are not genetically distinct from resident trout in their respective waters and switch to a fish diet later in their lifecycle.

Whether or not you view the ferox as a distinct species or not their scarcity and individual genetic characteristics must surely be deserving of enhanced conservation status to ensure their protection and conservation.

ANGLING

The very first thing you require in your box of tackle - should you be mad enough to decide the pursuit of the elusive ferox is for you - is to either already be - or quickly become - utterly relentless.

Without such dedication you will soon fall by the wayside for this path leads to hard days afloat in rough weather frequently chilled to the bone.

As for the actual fishing gear such decisions generally come down to personal choice however the following will give at least an indication of what is required to get you underway.

Firstly, to have any reasonable chance of connecting with a ferox you will need to get afloat as fishing from the shoreline - whilst you might get lucky - is simply not going to cut it long term so either buy, borrow or hire a boat.

If you have the luxury of a large wallet then both the Arran 16's and Orkney Longliners fit the bill very nicely indeed but so long as they are “sea worthy” – a phrase carefully chosen – most vessels can be pressed into service.

A medium to heavy rod fishing rod somewhere in the region of ten to twelve feet capable of handling heavy lures and dead baits.

A high quality reel with a decent drag system loaded with strong line of at least 20 lb. breaking strain as this will afford you the luxury of playing the fish hard and getting it to the net as quickly as possible so as to keep the stress levels of the ferox to a minimum and in so doing greatly improve its chances of survival upon release.

A fish finder so you can see contours and drop offs on the loch floor whilst simultaneously being on the lookout for any signs of large individual fish on the sonar.

A downrigger to get your lures and dead baits fishing at a controllable depth is pretty much indispensable.

As for end tackle such as lures and dead bait mounts they are individual choice with the one added proviso that you should not be afraid to use large lures and mounted dead baits.

TROLLING

If fishing a new water without advance intelligence then it may well pay dividends in the long run if you were to undertake a general reconnaissance sweep of the area with the sonar to try and identify any likely ferox holding areas such as underwater ridges or drop offs.

Once a likely area has been identified begin trolling at a relatively slow speed somewhere in the region of one to two miles per hour.

Keep a keen eye on your fish finder and should any ferox show then note their depth and set your own lure depths accordingly.

If nothing is showing then I would suggest beginning a sequence fishing your lures at different depths starting around the 30 foot mark.

Once a likely chosen holding area is covered then repeat at a slightly greater depth until hopefully contact is established with a ferox.

Remember ~ most ferox are captured at depths around the 30 to 40 foot mark.

Another often successful method is to “dead drift” a brown trout or perch suitably adorned with a one or two hook trace with just enough weight to take them down to any known ferox holding areas or alternatively simply to your chosen fishing depth.

Most importantly of all !

When it becomes patently obvious to all aboard that the entire loch is entirely devoid of any fish - far less ferox - your belief must not falter . . . remember !

Dream . . . Decide . . . Plan . . . Persevere !

THE SEASONS

Other important variable factors are the seasonal behavioural changes of the ferox themselves and the actual times of day that offer you the best chance of success when targeting these enigmatic fish.

During the early spring to mid season months of April through to May the ferox begin to throw off the shackles of their winter induced lethargy and start to become more active.

The mid summer months, June though to August, find the ferox dropping deeper seeking cooler water so set your baits accordingly.

September and October affords the intrepid autumn ferox hunter their best chance of success as the ferox begin feeding heavily before the onset of winter takes hold.

With these deep cold lochs now in the icy grip of winter during November through until March fishing often proves extremely challenging although a slow and deep presentation can occasionally save the day.